Let’s be clear, many folks have thrown-in. This question has loads of answers, and this writeup will likely not make it to the top of the search engines. So, what more is there to say? This: it’s not the answer that matters so much as is the philosophy that shapes it.

The answer — and, sure, let me be so bold as to say the right answer — is this: the difference between user experience and customer experience is scope. The customer is a category of user defined by the transaction. Not all users are customers; all customers are users.*

So, how as Metricians do we understand this question?

If we start with the core practical principle that the user experience is a metric, and if we agree to agree that our metric is some fuzzy holistic math — good or bad — we work to push up and to the right, then what’s the real function of using “user” as the adjective here?

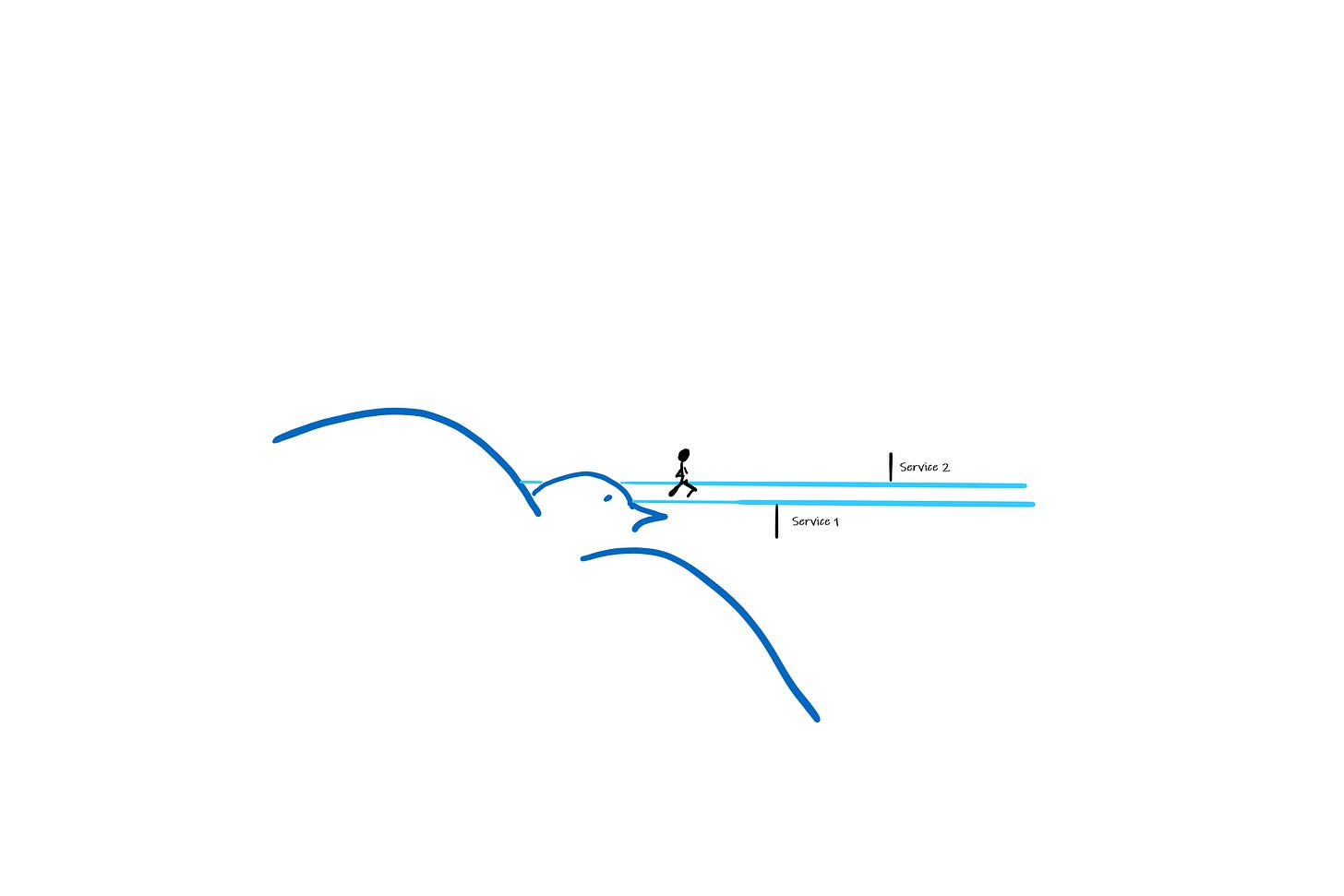

What we’re describing is the experience of a given role. Our users are people who, well, use our service. It’s an exercise in seeing just how vague we can be, but most of the time “user” works. When we’re working to understand our place in a larger ecosystem of services, imagined as a journey from a bird’s-eye view where a person moves from one service to another service to our service to another even further on in pursuit of some greater motivation, that they use our service is all we can really say for certain.

It’s only in the performance of designing for that user experience that, flying closer, we perceive the path isn’t solid but an obstacle course with touchpoints haphazardly spaced. The journey is an act not just of traversing from one to the other but the choice of how to traverse. These angles of approach — hopping, skipping, crawling, swinging — are variables in the fuzzy math that determine whether the user experience is positive or poor.

A variety of roles emerge on closer inspection, like looking at light through a prism. A single “user” early in their engagement with our service begins — let’s say — as a “subscriber,” for which we must consider the subscriber experience; they then pay to place an ad in some content, after which they become an “advertiser.” The advertiser experience includes a storefront and transaction, during which they too become a “customer.” A poor customer experience has detrimental impact on the user’s confidence in our service, part of which is defined by the quality of their experience as an advertiser. At no time, by the way, does this person stop being a subscriber.

What does it mean for the overall business when the customer experience is poor, the subscriber experience is alright, and the advertiser experience is good?

This downside-up rabbithole reality defines the UX problems inherent in news, where I presently spend the majority of my time. Ultimately, it is the “user” experience, that higher level fuzzy cumulative, that correlates with business success - but designing to keep that UX in the black is a strategic mess.

But this is true for you, too, wherever your niche. The awareness of this problem of scope is a mark of experience.

It is easy to conflate these roles I describe with personas, but they are not the same. A role in this way is defined by a job to be done that is contained within the motivating job to be done that set the user on this journey in the first place. The work is to first understand why folks use your service, then scope-in to identify the jobs within jobs: it’s how we design for those that ensure when users leave our realm for the next service on their journey that they don’t stumble on their way.

So, next time, when someone asks you the difference between UX and CX - you can now give them the choice to see how deep this rabbithole really goes.

* Some of you thinky service-design folk might write in that the one who pays for a service is not always the user of the service. I get where you’re going, but let me stop you right there. I think you’re wrong, but let me save the why for another writing.

Liking (❤) this issue of Metric helps signal to the great algorithms in the sky that this writeup is worth your time. Please take the time. If you haven’t already, please subscribe for free. Help produce this work for $5 per month — which, I swear, is the lowest Substack lets me go monthly — or $30 per year.

Metric is a podcast, too, which includes audio versions of these writeups and other chats. Subscribe to Metric on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Spotify, Stitcher, and all the usual places.

Remember that the user experience is a metric.

Your pal,

Michael

What is the difference between UX and CX?